Scales are perhaps the most basic music structure in any culture, together with rhythms. Any music student, whatever instrument he or she plays, would very soon start studying different scale types in all the tonalities the instrument offers. Jazz makes no difference with respect to other musical traditions: scales represent an essential tool for the improviser. There are many books and web pages that offer different interpretations of the relation between chords and scales. The key point, for the moment, is that scales can be seen the same way chords are: a powerful source of notes to choose from during the improvisation.

There are obviously many things to be said and questions to be asked about scales. For example: are scales useful to improve instrumental technique, or are other more specific exercises are more worthy? Do I need to study every conceivable scale or just a selection? On the recorder, do I have to study all tonalities or only the most commonly used in jazz (considering how difficult certain tonalities are on the recorder)? And so on...

I wish to start with a simple statement:

No matter what scales you study and how you do it, do it daily and learn them by heart.

I like to think of scales as big patterns for improvisation: when you use them during live improvisation, you simply don't have time to think of anything. They must be ready to be picked up at will. The only way I know to achieve this with any music fragment (whether it is made up of patterns or scales or chords) is to repeat them over and over, by heart, during a variable-but-usually-prolonged period of time.

Which scales?

There are literally tens of different scale structures. Just to name a few: Major, Minor, Whole tone, Pentatonic, Blues, Bebop, Diminished, Augmented, Gypsy, Hungarian, Japanese, Neapolitan, Persian, Arabic, Enigmatic, Pelog, Balinese, Hawaiian, etc.

For each structure named above there might be different versions each of which can also be played modally (i.e. changing the starting note): combinations are unnumbered.

While it is probably true that you could go on studying new scales for a lifetime, there are a few that have to be explored and possibly mastered as soon as possible. The following is my favourite scales list:

- Major

- Harmonic minor

- Pure minor (aka "Bach" scale)

- Whole tones

- Pentatonic

- Blues

- Dominant bebop

- Major bebop

- Diminished

- Chromatic

How to study

Here are a few considerations about scales in general, before going into each one individually.

a) Which instrument

The alto recorder is commonly considered the elective instrument to study technique. My advice is to study scales on your elective instrument, the one you intend to play jazz with, be it bass, tenor, soprano or alto.

b) Range

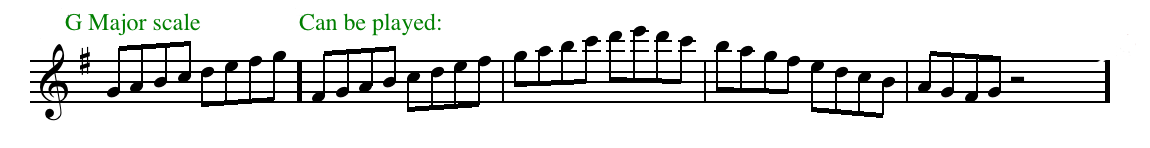

Almost all recorders, except a few "modern" ones, have the infamous problem of the F# in the third register (C# on C instruments): a note that can be taken only by closing the bell with a leg (there are exceptions, though). Scales need to be run through fast, so study them over the whole recorder range, from the lowest possible note to the highest, avoiding the closing of the bell. For example, study a G major scale on an F recorder starting from the lowest F# to the E in the second register.

In the meanwhile, do your exercises with the F# and the closing of the bell. Only once you feel comfortable with it, can you include that difficult position in your scale studies. In other words: don't slow down the scales because of bell closing notes! (Including all the other notes in the third register that require the closing of the bell.)

c) Tonalities

No matter how difficult it is, try to study all the scales in all tonalities as soon as possible. There will be huge differences between them at first: try to reduce them over time, aiming for an equal balance of intonation, sound quality and volume. You can do this through the usual techniques for difficult passages: repeat them with different rhythmic patterns, different articulations and at different tempos. So, on one hand you need to concentrate on difficult passages in difficult tonalities, but on the other hand make sure you play all the scales completely and over the whole range of the instrument. Don't put off learning difficult tonalities till doomsday: you need them now!

d) Patterns

There are many ways to study scales and many books to learn from. You can play scales with portato, legato or staccato articulations, by thirds, fourths, fifths and so on, with different patterns, in different sequences, etc. Like in the previous paragraph, my advice is: at first use all those different means to learn difficult passages, but eventually play all the scales plainly and over the whole range daily. Each scale, in each tonality has its unique "flavour", it's like a different room in a huge building: try to recognize that uniqueness in each of them.

Once you master all the scales in their plain version, then you can start playing them daily in other ways.

Major and minor scales

You can find these scales in any scale book for recorder, so I will not show them here. The only information to add is about the "pure" minor scale. Usually melodic minor scales are different upwards and downwards. This is not particularly useful, also because the downward version is a mode of a major scale. So, play it the same in both the ascending and descending orders.

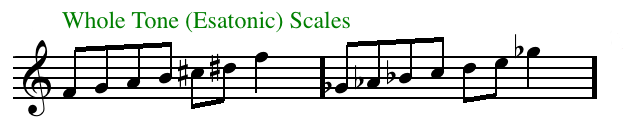

Whole tone scales

There are only two versions of this type of scale:

nonetheless play them starting from each note of the first octave and for the whole range of the recorder. For example, starting from C on an Alto recorder:

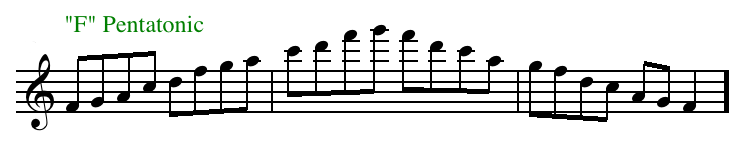

Pentatonic scales

There are a few different ways to describe pentatonic scales. My opinion is that it is not important to think of them as "major" or "minor" or whatever else you wish to call them. Pentatonic scales are intrinsically open structures that can be fitted in an infinity of different musical situations, so it is better to know them in all their tonalities and combinations. A first pentatonic scale on an Alto recorder could be:

Transpose this structure all over the first octave and play it over the whole range. For example, starting from Db you would have:

(Don't fret: this is one the most difficult pentatonic scales!)

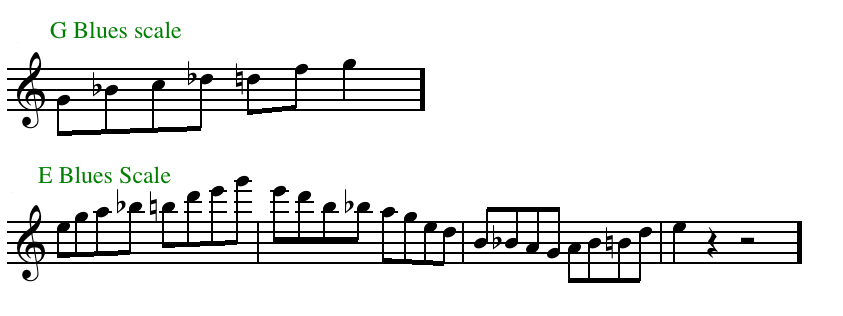

Blues scale

The Blues scale is sort of the "salt" ingredient of jazz improvisation: when used appropriately, it enriches the "taste" of your improvisations. Again, you can find many different versions of blues scale, but the following is my favourite:

In the example above you can see an E Blues scale played all over an Alto recorder range.

Bebop Scales

This type of scale was derived from the long improvised lines of Charlie Parker and friends, hence the name. There are a couple of Bebop scales, namely:

There are two main reasons to use these scales:

- They add some chromatics around key notes (i.e. 7th and 5th grades)

- Being composed of eight notes, they can be played as a scale on 7th chords, leaving chord tones on the beat. For example, on a C7 chord you can use a C dominant bebop scale:

Diminished scales

A diminished scale is built by alternating semitones to tones. This way you can have only three different scales, for example:

Even if there are only three scales, study them by starting from each note of the first octave and going over the whole instrument range, like in the esatonic scale example.

You can easily verify that each single note in the chromatic scale belongs to only two diminished scales: the one starting with a semitone and the one starting with a tone. Study them in both ways so as to play 24 "modes" of diminished scales in total.

These scales are particularly useful with dominant and diminished chords, and as a junction across modulations.

Chromatic scale

As most readers will already know, this scale contains all twelve notes, or semitones, in an octave. So, considering what we have said so far, a chromatic scale to start with on an alto recorder would be:

As usual, play it by starting from each note of the first octave and going over the whole instrument range. In any case, I find that studying the chromatic scale this way (and downwards of course) is not enough for improvisation. Try to fragment it into smaller pieces, for example:

Here an augmented fourth is covered, but you can use different, smaller or broader, intervals, starting as usual from each note of the instrument (in this case even in the second octave, like in the above example).

Daily sessions

According to what we have seen so far, you should end up playing daily the following scales:

- Major

- Harmonic Minor

- Pure Minor

- Whole Tone

- Pentatonic

- Blues

- Dominate Bebop

- Major Bebop

- Diminished 1 (starting with semitone

- Diminished 2 (starting with a tone)

- Chromatic.

A few answers

We started listing a few questions about scales: I will now try to sketch an answer for each of them.

- Are scales useful to improve instrumental technique, or are other more specific exercises more worthy?

On the one hand, I think scales are like a "thermometer" of your skills. If they work, your technique is working; otherwise you should take a step back to more specific exercises to solve single problems. On the other hand, speaking of jazz improvisation, scales (and chords) are your technique, so they are more than just useful: they are essential.

- Do I need to study every conceivable scale or just a selection?

I think I have already answered this: the type of scales outlined here are what I consider a minimum set to be mastered. All other scales can be added later, either to emphasise certain type of chords more specifically, or to add some "exotic" flavour to your improvisation. - On the recorder, do I have to study all tonalities or only the most commonly used in jazz (considering how difficult certain tonalities are on the recorder)?

This question hides a lack of perspective. If you look at tonalities of standards, there are certain keys that are more common than others. However, during improvisation you should always be ready to jump to other tonalities, for example by shifting one semitone up or down, or following some chromatic turnaround. Even in a piece in C major you could end up touching all twelve major keys during an improvisation.